A Documentary Pioneer

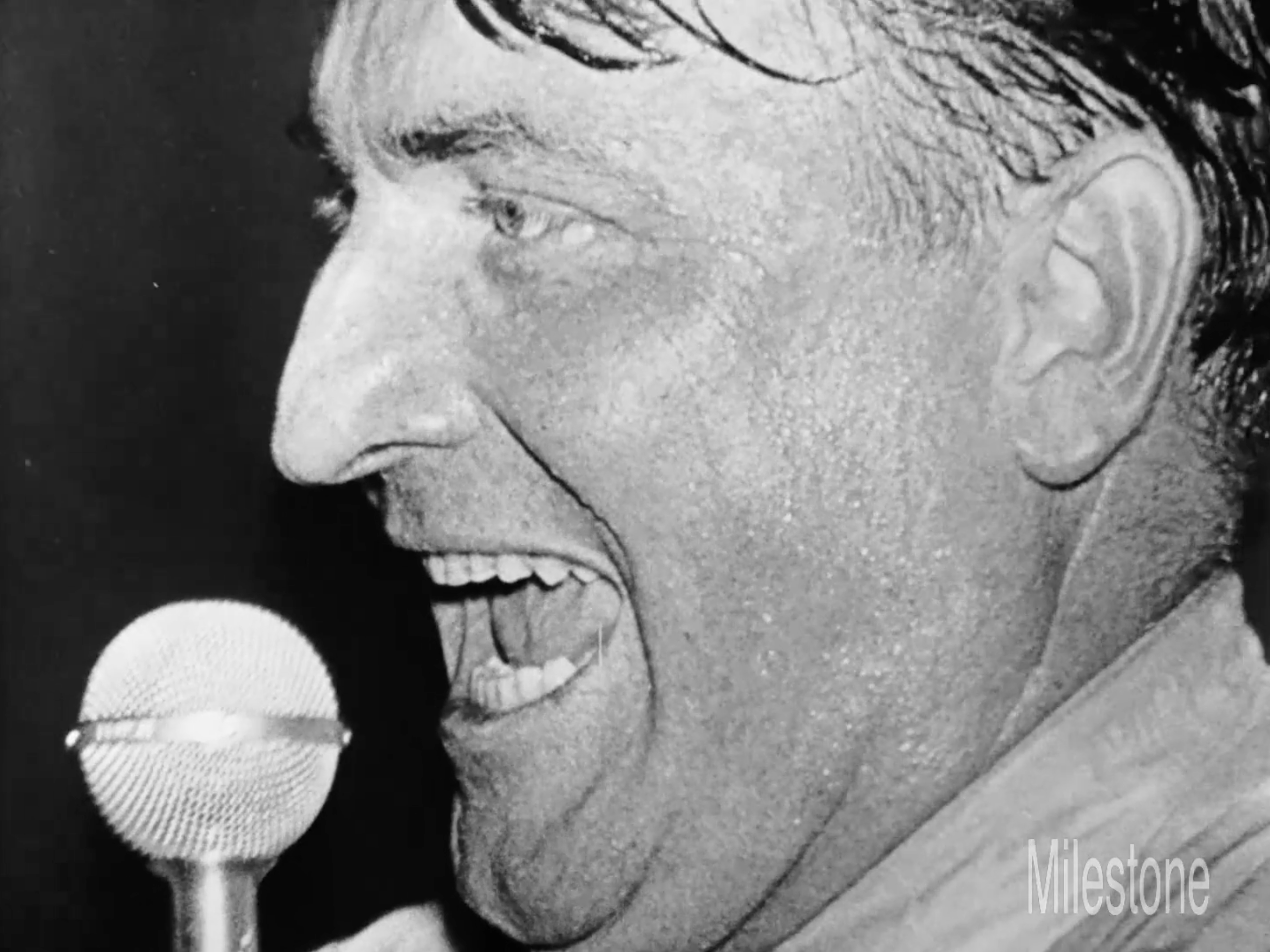

Honoring Filmmaker Leo Hurwitz

Pioneering Documentarian & Advocate for Truth

Leo Hurwitz (1909-1991) was my great-uncle. In this section on Characters on the Couch, I write about Leo Hurwitz’s Filmography and honor his contributions to the field of documentary film-making. Leo played an important role in the origins of documentary film in America. In fact, he took documentaries from newsreels to the social documentary form in the early 1930s with a handful of other documentary filmmakers including: Paul Strand, Ralph Steiner, Sidney Meyers, and Elia Kazan.

On this page, you will find a list of Leo Hurwitz’s filmography with links to a series of pieces I wrote in 2017 about a number of Leo’s most important films. They’re posted here on this site on my Characters on the Couch blog and are highlighted below in bold. You will also find links to watch the films on Leo’s website, created by his son, Tom Hurwitz.

My first three pieces are historical and set the stage for Leo’s life and work: Part 1, Leo’s History: Family Influences (READ HERE); Part 2, Leo’s History: Childhood Memories and Fantasies (READ HERE); Part 3, Leo’s History: A Radical Filmmaker in The Making (READ HERE). The fourth is a piece on Leo’s two psychoanalyst sisters, Marie H. Briehl and Rosetta Hurwitz, also pioneers in their own right, in the psychoanalytic world I myself now live and work in (READ HERE).

My historical articles are followed by pieces on Leo’s major films. My pieces are based both on the films themselves and on my personal musings. They’re my way of honoring the work of my great-uncle. I extend my thanks to psychoanalyst Arnold Richards, M.D., also an activist who knew Leo, for inspiring me. For making the films available, a very special thank you to my cousin Tom Hurwitz, Leo’s son and himself a cinematographer and documentarian, as well as to the late Nelly Burlingham, M.D., Leo’s widow. And, another thank you to filmmaker Manny Kirchheimer, Leo’s colleague and friend.

Leo’s History & Blacklisting

Leo Hurwitz’s creative documentary work came first out of his involvement with the Workers Film and Photo League in New York City in the early 1930’s.

As a socially conscious documentary filmmaker, devoted to human rights and exposing the fascist forces that undermine basic human freedoms, Leo’s early films (Heart of Spain, Native Land, and Strange Victory) particularly addressed these concerns. Later, the House Un-American Activities Committee blacklisted Leo during the McCarthy era, known as the “Second Red Scare,” lasting from the late 1940s through the 1950s. Leo was blacklisted for his affiliation with the Communist party and, although his filmmaking and creative work never stopped, many doors were closed to him. He worked in the shadows, during these years, as many of those blacklisted did, undercover and under aliases.

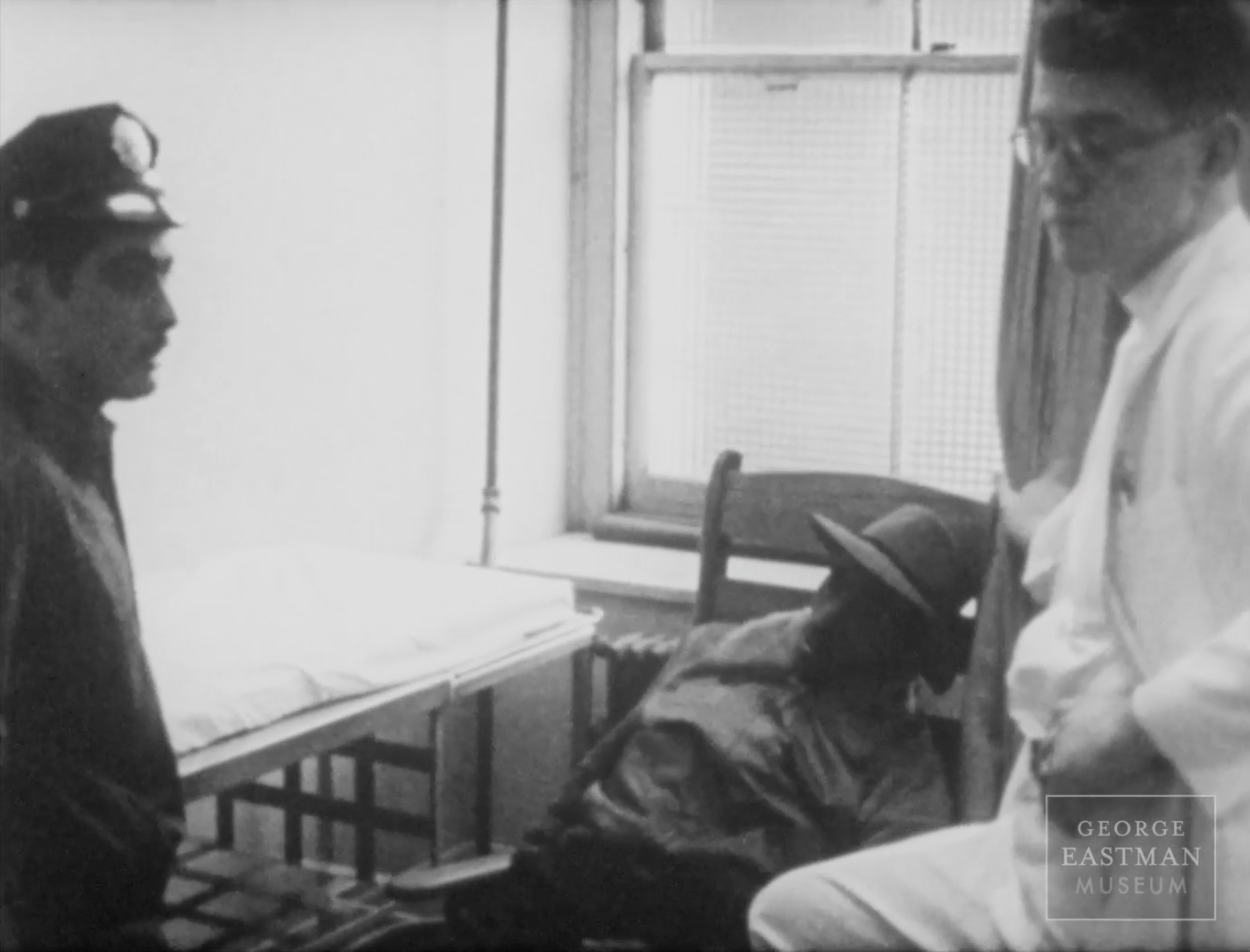

In spite of his blacklisting, Leo did complete some of his major works during the McCarthy period, between the years 1949-56 and in 1961. Each film was produced and financed differently: Young Fighter, 1953 (hugely important in the development of cinéma vérité); Museum and the Fury, 1956; Here at the Water’s Edge, 1961. Even USA, 1956, produced for Pan American and used by the United States Information Agency, was innovative in its implementation of photo animation and folk music.

Because Leo was blacklisted from working under his own name in television, Hollywood motion pictures, and usually in the industrial documentary field as well, he made Young Fighter for CBS, using a front; the film’s cameraman. The Polish Government commissioned Museum and the Fury. Charles Pratt financed Here at the Water’s Edge. The production company for the Pan American film USA brought Leo on to fix a totally broken film, which he did brilliantly. Finally in 1961, Milton Fruchtman and a small production company named Capital Cities hired him to direct the television coverage of the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. The blacklisting was over.

Vijay Seshadri Describes Leo

Before you begin reading my accounts of both Leo’s history and films, I want you to have a vivid picture of Leo in your mind.

Here is his friend Vijay Seshadri’s description of Leo Hurwitz, the man, from Seshadri’s moving memoir of their relationship, Which Side Are You On, Boys? The American Scholar Vol. 70, No. 2 (SPRING 2001), pp. 49-62.

“He had a short, solid body, which combined with his no-nonsense discursive style and his habits of indignation to leave the impression of overall bluntness, an impression mitigated by the look of keen rationality in his eyes and by his head and face, which were long and carefully sculpted, and would have been described in the nineteenth century as “fine.” But this was just his body. Inside this physical frame there lived, waiting to spring forth, the unresting champion of the poor and downtrodden, the immemorial working-class hero, intellectual-workers’ division—dissident, disenchanted, morally fervent.”

Leo’s Filmmaking

Leo’s filmmaking spanned a period of almost sixty years, from 1932 until his death in 1991.

He toured the world with his much-acclaimed film, Dialogue with a Woman Departed, completed in 1980, and worked on other projects, including a film about miners with his son, Tom, partly shot and edited. From about 1985 on, he had NIH funding and a panel of experts for a script called “In Search of John Brown.” The script was largely completed and he was working on its next steps at the time of his death.

All of Leo’s films have his particular stamp of deep poetic creativity intermixed with a passion for seeing and never forgetting the truth. Below is a chronology of Leo Hurwitz’s work in documentary film. The highlighted films I’ve written about have a brief introduction with a link to READ MORE. Each film also includes a link to watch free at leohurwitz.com. The films are a treat not to be missed. His early films are timely, addressing many of the problems and concerns we live with in the United States now.

Birth of Social Documentary (1932-1937)

Films of Protest & Truth (1937 – 1948)

First Cinéma Vérité (1951-1956)

Films of Life & Death

Films of Art & Seeing (1968 – 1980)

Film of Love & Loss (1980)